I've got a question about Japanese that I'd like to address to the experts (Tae Kim, I hope you're listening!). Most Japanese grammars present the formal desu/ -masu forms and the regular forms as a dichotomy: you pick one and use it 100% of the time with a certain person or you pick the other and use it 100% of the time with that person. The thing is that a lot of native Japanese speakers mix up the two in actual usage with the same person. My question is what rules do these follow? When can you throw in a few informal forms in otherwise formal speech and vice versa? There seem to be a variety of conditions for this, but I've never heard anyone try to explain it. Read more...Sometimes the reason for such mixing is clear. For instance, friends who otherwise never use the formal forms with each other will sometimes use them jokingly, creating an effect of feigned formality that can often be used for sarcasm. Parallels to this usage can be found in all the languages I've learned; think of using "Would you be so kind as to pass the bread?" to your boyfriend of girlfriend. You're either joking or annoyed.

But there are other times when it's not so clear.

For instance, my Japanese father-in-law typically only uses the informal forms with me. But he'll sometimes throw in the desu/-masu forms as well. It's probably more than 95% informal forms. He seems to use the formal forms when he wants to emphasize a point, and typically it's either a desu yo or a -te masu. Sometimes it doesn't seem like it has anything to do with making a point. For instance, if I say something like, "Can I borrow this?", an informal way to say "Sure" would be "Ii yo", but he might say "Ii desu yo". While that sounds more formal, it certainly doesn't feel more formal, and he'll whip right back into the informal forms on a dime after that. My mother-in-law and him also often will toss in formal forms when they are speaking to each other in roughly the same manner.

Another instance I encountered was on the train a few days ago. I was sitting down and two guys got on and were standing in front of me talking. Based on how old they looked and what they were saying, I got the impression that they were college kids, one younger than the other. The younger one was generally using the formal forms while the older one was generally using the informal forms. That is typical enough. However, while the older one didn't seem to include any formal forms, the younger one would on occasion include some informal forms.

It's clear that the use of these forms is not a complete bifurcation. There are shades of gray, in which you can throw some informal forms in with formal forms and vice versa, and I'd love to know what the rules behind this are.Labels: Japanese

Kelly of Aspiring Polyglot left this comment on my earlier post about how to say "China" in Russian and Japanese: Would you happen to know why we call Japan 'Japan' and not Nihon or Nippon? This is one that I dug up a long time ago because I wondered the same thing. The kanji for "Japan" are 日本. They respectively mean "sun" and "origin", or together "origin of the sun". This is of course from the perspective of China, to the East of which Japan lies in the same direction as where the sun rises. That's also where English gets "land of the rising sun" from, which is simply a more nuanced translation of the characters than "origin of the sun". Read more...The word in Japanese is pronounced Nihon or, with a bit more emphasis or formality, Nippon. Nihon is actually a relatively recent shortening of Nippon, which in turn is a shortening of the readings of the two characters following normal character combination rules. 日 can be read nichi or jitsu in this case, and nichi is preferred here, while 本 can be read as hon. Typically, when two character are adjacent to each other in a single word, the first ends in chi or tsu, and the second starts with h-, the chi or tsu is dropped, the consonant doubled (or っ is added for all of you who are beyond romaji), and the h- becomes a p-. You thus get Nippon. You can also see the pattern in, e.g., ippon (一本, いっぽん, "one long, slender object") combining ichi and hon, or in happyaku (八百, はっぴゃく, "eight hundred") combining hachi and hyaku.

Once I had figured all this out when I was first studying Japanese, I thought I had figured out where "Japan" came from as well; obviously people had just used the other reading for 日 at some point, i.e., jitsu, which would have resulted in a reading of Jippon, and that's only a linguistic hop, skip and a jump away from "Japan".

As it turned out, I was on the right track but not quite there.

Nihon and "Japan" ultimately share the same etymological roots, but the path to the English word isn't very clear. It's believed that it came to English via one of the Chinese dialects' pronunciation of the characters 日本. It's these same pronunciations that likely supplied both the j in jitsu, and in "Japan", so my guess was a wee bit too high in the etymological tree.

Marco Polo called Japan "Cipangu", which, in Italian, would be pronounced like "Cheepangoo". (The gu is from the Chinese character 国, meaning country or kingdom, and which is currently pronounced guó in Mandarin.) This is thought to have come from a Wu dialect like Shanghainese. The Portuguese also brought words like Giapan over to Europe, which ultimately led to the English word. Below are a few of the Chinese dialects that might have been involved and their modern day pronunciations of Japan:

| Cantonese | Jatbun | | Fujianese | Jít-pún | | Shanghainese | Zeppen |

Links:

Names of Japan on Wikipedia

Japan in the Online Etymology DictionaryLabels: Cantonese, Chinese, Chinese characters, dialects, English, Fujianese, Italian, Japanese, kanji, Portuguese, romaji, Shanghainese

I'm currently on a plane on my way to Tokyo for a week-long trip there followed by a week-long trip to China. Sitting here, it's obvious what a useful environment for language learning your flying time can be; the by-necessity multilingual environment of a flight to another language zone means you can easily get some exposure to your target language while in transit that probably isn't always readily available outside of where the language is spoken. Read more...The first opportunity you'll come across are the flight attendants, who will probably be there to greet you when you get on board. Greet them in your target language, and if you've got any questions, try to ask them in the target language. They'll probably initially make assumptions about what language you speak. On a flight like mine from New York to Tokyo, Japanese-looking Asians will be initially addressed in Japanese and everyone else will initially be addressed in English, if the flight attendants have the language skills. I'm on a Japan Airlines flight, so most of the flight attendants are Japanese but of course all of them also speak English. Before I said anything to them, they predictably spoke to me in English, but once I spoke to them in Japanese they switched to Japanese. Some of them seem to be prefer Japanese when possible, and I'm more than happy to accommodate. You'll sometimes find that even if you speak your target language, they'll still won't use it back to you, but be stubborn; don't switch back just because they don't deem you target language worthy. Some flights will not have so many target language speakers, such as my typical Continental flights to Japan. In that case, you can direct any questions you have to those who speak the target language.

Although you're more likely to need to communicate in some way with the flight attendants, your fellow passengers are another good source for target language exposure. There's probably a pretty good chance that the person sitting next to you is a target language speaker. Find a way to strike up a conversation. Unfortunately, the person I'm sitting next to right now is a bit reticent and has been sleeping most the time, but on other flights I've had great conversations with those sitting next to me.

When they come around with reading material, grab something in the target language. Even if you're not that strong in the target language, get a newspaper or the like and see what you can understand. A few words here and a few words there might be all you can get, but it's nevertheless more exposure. There's also some reading material in the seat pocket in front of you and on signs around the plane. Although safety instructions and the like might not be the most exciting things in the world, they're usually in the target language and one or more other languages, so you've probably got a translation already sitting right in front of you.

The onboard entertainment is another good source. It will typically be in multiple languages, either with target language audio or with target language subtitles. Watch some of these to see what you can pick up, or if you're getting it all just sit back and enjoy.

And, of course, don't forget to be a good little Boy Scout and "be prepared". With a laptop, iPod, electronic dictionary, and an array of other possibilities, you can make that "wasted" flight time quite productive.Labels: English, Japanese, language zone

Today I came across Китай ( Kitay), the Russian word for China. Curious as to how China ended up with that name in Russian while most other languages that I'm familiar with have a form similar to English, I guessed that it was related to the English word Cathay and Wikipedia appears to have confirmed that for me. They both seem to trace their roots back to Qìdān (契丹), which I'll wager was pronounced "Kitan" or the like back in the day. If you that's not enough useless knowledge about what China is called in various languages, then I've got one more for you. In Japanese, China is generally called Chuugoku (中国), but they've got a couple of versions like "China" as well, one which is A-OK and the other which is taboo. The one that's fine to use, and is even kind of cute, is just taking the word from modern English: Chaina (チャイナ). Like many English words, the Japanese flexibly stick it into their script and then use it freely, if informally, although the only place I've heard it commonly used is in a contracted form to say Chinese: Chaigo (チャイ語). You'll particularly hear college students use this one when discussing studying languages, and they do the same sort of contraction with other languages as well. For instance, "French" becomes Furago (フラ語) instead of the full form of Furansugo (フランス語). The term you don't want to ever use in Japanese is Shina (支那). Although the mayor of Tokyo might beg to differ and has been known to use it, it is generally offensive to Chinese people due to its wartime use, despite its uncontroversial origins dating back to Sanskrit (read the whole story here). Labels: Chinese, Japanese, Russian, Sanskrit

For those of you that haven't stumbled upon it yet, Tim Ferriss's blog is quite an interesting read, but I am of course most interested in his posts about languages, the best of which are: Once I get through Street-Smart Language Learning, you'll quickly see that I agree with almost all of his ideas. And, courtesy of Tim's blog, here's a bonus link to a good article on frequency lists: Why and how to use frequency lists to learn words by Tom Cobb. Related: Top 10,000 words in Dutch, English, French, and GermanWord lists based on frequency of useLabels: English, language classes, Spanish, word frequency

Bilingoz (via Aspiring Polyglot), the brainchild of Mark MacIntyre, a Canadian who has logged nine years in Japan teaching English and finding the existing tools insufficient to teach those with a need for specialized vocabulary, is a study aid for English speakers in need of specialized Japanese vocabulary (or vice versa, I suppose), such as accounting, dentistry, metallurgy, etc., and one in particular that attracted a lawyer like me: law. So I kicked the tires by testing out my knowledge of basic Japanese legal terms, which (thank goodness) I seem to know pretty well. Read more...Here's what you can do on Bilingoz:- "Study", i.e., play a matching game in which you are presented with a six-by-five grid, with each square of the grid containing either Japanese or English. You must then match up the squares, similar to the child's game Memory.

- Take a "quiz", i.e, do a multiple-choice quiz, which randomly selects wrong answers from the English translations of other vocab.

- Listen to an audio recording of the words in Japanese at the basic level (i.e., their least advanced level). This is incredibly convenient and will save you a lot of time when you can't recall how a character is pronounced. Hopefully, they'll be added to the more advanced levels sometime soon.

And that's about it. Not quite a one-trick pony, but not far from it.

The exercises suffer from the process of elimination problem, which I've discussed before; because you can use testing strategy to eliminate answers, you can often figure out the right answer without really recognizing the word when you see it. I confess to finding the Memory-like game mildly entertaining, but I don't think it would be as effective as a more standard flashcard-based system. I'd love to see them add traditional flashcard review as an option. game mildly entertaining, but I don't think it would be as effective as a more standard flashcard-based system. I'd love to see them add traditional flashcard review as an option.

The other big downer is that it doesn't record your progress. You don't log in, so there's no record of what you have or haven't studied, meaning that you'll probably repeat words you already know in the exercises while trying to cover those that you don't.

Nevertheless, the vocab lists are of high quality; I wish I had them when I first began learning Japanese legal terms, because using these tools could have saved me some time. And the pronunciation recordings at the basic level are quite convenient. While the tools leave something to be desired, they are not without their utility and I'd recommend Bilingoz if you need specialist vocabulary in one of the categories covered.Labels: English, Japanese, specialized vocabulary

To get back to the theme of ethnic experiences in the U.S. that I touched on earlier, many of you in the U.S. or Canada may remember from your childhood that you, if you're Asian, or your Asian friends always had to go to school on Saturday. While the rest of us were getting our brains rotted out by Saturday morning cartoons, Asian kids' parents forced them to do more school, as if any kid thought five days wasn't already enough. Those forced to go never seemed very happy about it, and often rebelled and stopped going when they got old enough to pull it off. As much as these kids may have been unhappy during classes, those who actually ended up sticking with it ended up (hopefully) thanking their parents, because they were probably pretty darn good at the languages that those classes were teaching them. My daughter, age four, just kicked off her experience with this Asian-American tradition with Saturday Chinese school (yes, that is despite her Japanese mother and her Italian-American father). We recently discovered that there's one of these schools about ten minutes from our house and, although we missed the first semester, we were eager to get her started and finally got around to it today. While she's had Chinese nannies and babysitters for most of the time that she's been speaking, we found that she was progressing a lot more in English (she goes to English nursery school every day, karate once a week, and dance occasionally) and Japanese (she goes to Japanese Kumon classes twice a week and ballet once a week) than in China, whereas Chinese was originally her best language (she started speaking while we were in China). As it turns out, her Chinese classes here are as much of a language experience for her as they are for my wife and me. Read more...One of Felicia's babysitters had called the school this week to see what we needed to do to get her enrolled, as their online registration wasn't working. He basically said just go there at 9AM on Saturday to take care of whatever paperwork there was, and she should be set for class at 10:45AM.

We show up at the middle school where the classes are held to see a parking lot full of Chinese people (they were probably mostly or at least partially Chinese-American, but let's just keep it simple and call them "Chinese"). We then go into the cafeteria, which was something of a base for the classes and a gathering places for pretty much every one related to a kid attending any of the classes, and this too was chock full of Chinese people with an occasional white person (case in point) floating around. In the typical entrepreneurial Chinese style (that somehow, amazingly, Mao managed to suppress for a few decades last century), one person set up a store of various snacks and drinks on one table, looking like they had just bought bulk and driven it straight over here. And some of the scenes there were straight out of a movie like The Joy Luck Club, such as the cafeteria table claimed for a game of mah-jong by a group of grandparents, with grandchildren running around at their feet.

We wandered around the cafeteria for a bit and weren't sure who was in charge until someone started setting up a printer and a scanner at a desk near what I suppose was supposed to be the front of the cafeteria. So we walked up to them to inquire about what we needed to do.

We thought there might be a little issue about our daughter starting in the middle of the year, so my wife, who thinks I'm a better negotiator, had me do the talking. Although I'm pretty sure they all speak English just fine, I opted to use Chinese because of a concern about the classes. There's a Chinese class for Chinese speakers, like my daughter, and another for Chinese learners, i.e., English speakers who are starting to learn Chinese. I was concerned that they'd see my white face and think, "Oh, here's another one for the foreigner's class," and so I hoped to evade that discussion by going at them in Chinese. Doing that, they would assume that my Japanese wife is Chinese and then just put my daughter in the class that promises better language exposure by not using English (although the teacher did keep saying "sticker" in English while speaking Chinese in lieu of the perfectly available Chinese word tiēzhǐ). Sure enough, the mid-year start date was raised as an issue. We weren't concerned about my wife speaking up either, because her accent's good enough that she falls within a range that sounds Chinese, and Chinese people are always generically asking, "So you're from Southern China?" when they hear her talk.

Their first answer was, "No, we're full,", but one thing I found to be true in China was that, if someone initially said no to you, persistence could turn that into a yes, and I intended to see if the same thing worked here. The rational analysis sometimes seemed to be, "Is it less of a hassle to just say yes to this guy or to keep saying no?" If they say no and you just walk away, that's a piece of cake for them, but if you make a nag of yourself suddenly it becomes easier to just let you do whatever you want. (This is something I discovered as a kid worked with my parents too, but I'd rather my kids come up with this idea.) For instance, when I was studying Chinese in Beijing, the placement test put me a level or two below the top of maybe a dozen levels, but I wanted to be in the highest level possible because of how rapidly you can learn when you're immersed. When I was first told no, I kept bugging the person who told me no and several other people until I finally got bumped up, clearly above what the test results had gotten me. I'm not sure if this works in all bureaucracies in China (unfortunately, in some, a wad of cash will work much better), but it usually worth a shot.

The first answer we got from the Chinese administrator was, "Sorry, it's the middle of the year, we're full." So I said that we had called earlier this week and they said to show up at 9AM and we should be able to take care of everything. He asked who we spoke to and, since the babysitter called, I had no idea. I did know, however, that it was "the guy whose name and number were on the website", and I told him so. Apparently he had no idea who that was. After effectively repeating this interchange a few times, he finally gave in. I think he might have thought that the person our babysitter had spoken was someone important that was higher up in the administration, so he was weighing potentially needing to deal with that guy or just letting us sign up. He went for the signing up.

So we take care of the paperwork and whatnot and we're sitting in this cafeteria full of Chinese people. And then my son reminded me what good language-learning tools one-year-old kids can be; my son kept going up to people and pointing at them, and this would repeatedly result in them calling him cute and start talking with us.

My wife eventually left to run some errands, leaving me to escort our daughter to class. After dropping her off and again getting a chance to converse in Chinese - this time with the teacher, I was left alone. There happened to be free Chinese-langauge newspapers there so I picked one up and started reading it. It appears that the de facto standard Chinese in the U.S. uses traditional characters, and there were a few that were driving me nuts because I was sure I knew them as simplified characters but the traditional versions weren't ringing any bells. In any case, one of the articles I read was criticizing China's stimulus plan, saying it only helped bureaucrats' favored companies, while the U.S. stimulus plan was aimed at the average person. A pretty interesting read, but it was a shame I didn't have my dictionary with me because now I have to go back and reread it to find all the words I didn't know, if I even end up bothering to do so.

Today also happened to be the day of what they called "parent-teacher conferences", but were less the one-on-one meeting that that term conjures up than the teacher giving an update to all the parents at once. So I got to sit through my first such meeting in Chinese today, and I was surprised at how easily I was able to follow what she was saying. There were only two words I didn't get, but since they are things that the kids will be doing this upcoming semester (I got that much), I'll probably be learning the words soon enough.

So now we have a chance every Saturday to hang out in a hall full of Chinese speakers, and as my daughter makes friends and we meet people there, I'm sure we'll be putting our Chinese to great use. This is just one example of the many creative ways that you can find people to chat with, if not outright native-speaker tutors, and also get other kinds of exposure to your target language in less-than-obvous places far from the language zone. If you had asked me where I could find hundreds of Chinese people gathered together every Saturday in the New Jersey burbs just a month ago, I'm sure I would have had no idea. But now that I have found just that, it's definitely a great language-learning opportunity for all members of my family - and not only those for whom we're paying tuition.Labels: children's language learning, Chinese, Chinese characters, English, Japanese, language zone, native-speaker tutor

After my wife read this post, she started telling me about what might amount to an interesting trend. After noting that she herself prefers to argue in English rather than in Japanese, she said she heard the same thing from her Japanese-speaking American professor about his English-speaking Japanese wife. He told her that typically he'd be using Japanese while she'd be using English when they argue. She cited two reasons for why she prefers English. The first, which I don't buy so much, is that English has more appropriate curse words to throw into the mix. I would agree that English has a leg up on Japanese in the curse word department, and we certainly use them a lot more, but Japanese attains the exact same effect through intonation and certain verbal forms rather than adding colorful vocabulary to the sentence. For instance, the standard, informal way of saying, "What are you looking at?" would be " Nani miteru?", " Nani miteru no?", with the no making it a bit softer, or " Nani miten no?", with the swallowing of the ru to an n making it sound more informal. You start to sound unhappy when you say, " Nani miterun da?" or, with a bit more oomph, " Nani miterun da yo?". When you're even more unhappy, so unhappy that you can't even say the whole thing, then it'd become " Nani miten da?" or, with oomph, " Nani miten da yo?" Depending on how it was said, that last one might be translated as "What the hell are you looking at?" To upgrade that to the equivalent of a stronger four-letter word in English, you would just make the intonation more angry, forceful, and emphatic. The second reason, which makes a more sense to me, is that she said that when she switches languages, she switches cultures as well. I can relate to this better, as this is something I do as well. When visiting a friend in France with whom I had studied in Japan, she joked that she could tell what language I was speaking - English, French, or Japanese - without even hearing what I was saying due to the change in my mannerisms. As for arguing, Japanese culture is quite a bit less confrontational than our barbaric Western culture, and argumentative females remain a relatively rare species in Japan, so the cultural switch leaves her at something of an arguing disadvantage. So I'm curious... has anyone else encountered anything like this in a multilingual relationship? Labels: English, Japanese

When you think logically about where to draw a line between a dialect and a language, it would seem that the place to draw the line would be at mutual intelligibility. If the way two groups of people speak is mutually intelligible but somewhat different in pronunciation, word usage, etc., you're looking at two dialects, whereas if those two patterns of speech are not mutually intelligible, you're looking at two languages. This standard would generally work well as a rule of thumb. American, British, and Australian English would all be dialects, as would the Kantou and Kansai dialects of Japanese, while Spanish and Portuguese would be languages. However, such a division won't always hold true in all languages, and the big example I'm thinking of is Chinese. Read more...China is a country full of what I, and apparently most linguists, would call languages. They are all for the most part related Sino-Tibetan languages, but as they are generally mutually unintelligible I'd classify them as languages. Indeed, the English of most of these end in the "-ese" suffix, designating them as languages rather than dialects, e.g., Cantonese, Shanghainese, etc. However, in Chinese they are referred to as fāngyán 方言 ("dialects"). When referring to them directly, Chinese will often use the -huà -话 (roughly, "speak") suffix, which usually designates a dialect, e.g., Guǎngdōnghuà 广东话 ("Cantonese"), Shànghǎihuà 上海话 ("Shanghainese"), etc. Other examples of where this -huà -话 is used to designate a dialect are Pǔtōnghuà ("Mandarin", or literally "normal speak") and Měiguóhuà ("American English", or literally "America speak"). In contrast, the suffixes -yǔ -语 and -wén -文 are generally used to designate languages, e.g., Hànyǔ 汉语 ("Chinese", or literally "the Han language"), Zhōngwén 中文 ("Chinese", or literally "the Chinese language"), Yīngyǔ 英语 and Yīngwén 英文 ("English"), etc.

I often compare Chinese "dialects" to the Romance languages. The differences between Chinese dialects and the Romance languages are similar. The spoken word is generally mutually unintelligible, but you'll be able to pick out at a minimum some words and phrases. They all share a vast vocabulary base, although pronunciations often vary to the point of mutual unintelligibility. Grammar is extremely similar, so if you ever do need to learn another, you'll have little problem doing it. If you know one, you can do a pretty good job of reading another. Indeed, the two words above for Chinese emphasize this fact; -yǔ -语 emphasizes the spoken language, and hence is linked with the Han group and how they in particular speak, while -wén -文 emphasizes the written language, and hence is linked with all of China because of how the written language can largely be understood anywhere in China regardless of the dialect you speak.

So why is one called a dialect and the other a language? Although I'd venture that the gap between the Romance languages might be a bit bigger than the gap between the Chinese dialects, it seems to me that history and politics are at the heart of it. Europe has long been divided into countries, each more or less with its own language, stressing the difference. China, on the other hand, for whom national unity has been a long historical struggle and remains a core policy of the government, prefers to stress the oneness of the Chinese language while downplaying the differences that these dialects actually represent. But, if you consider them dialects, then you can make a pretty strong argument that the Romance languages are dialects of Latin. And if you consider the Romance languages to be languages, then, vice versa, you can argue that the Chinese dialects are mostly separate languages as well.

What does a language learner take home from this? If you speak Mandarin, don't think you're going to nail down Cantonese as easily as you'd go from American English to British English just because it's called a dialect. At the same time, don't think that the differences between Portuguese and Spanish are so great just because they're called separate languages. If you really want to know how far two languages/dialects are apart from each other, talk to some speakers of both languages are take a look at some language family trees, which can be found aplenty on Wikipedia.Labels: Cantonese, Chinese, dialects, English, Japanese, Portuguese, Romance languages, Shanghainese, Spanish

As you might know, I grew up in an Italian-American family in a suburb of Philadelphia. I don't know if this is something that all Italian-American kids run into, but one day my dad sat me down and - I kid you not - told me that I was never to get involved in the mafia. I thought he was kidding and kind of laughed it off, but he was quite serious. I think this may have been a real concern for people of his generation, having grown up in heavily Italian-American parts of Philly in the 1940s and 1950s, and I had the feeling that this was a talk his own dad had had with him at some point. But, as the good little suburban Eagle Scout that I was, I didn't have the first clue about how to join the mafia and the idea was so foreign to me that my dad's little sit-down seemed downright silly. So it was with much amusement today that I got berated by my wife for speaking like a mafioso. We've been watching through The Sopranos together lately, but I can tell you with absolute certainty that it wasn't the influence of The Sopranos that had me talking like a mafioso, because my wife was complaining about me doing it in Japanese - not English. We had our little spat in Japanese, and apparently I started sounding like a yakuza, i.e., a member of the Japanese version of the mafia. Read more...However, I do know where to lay the blame. Japanese movies and television featuring yakuza characters, as well as manga that I read while learning Japanese in high school, share some of the blame, but I lay most of it on the shoulders of a good Japanese friend of mine (who shall remain nameless, although my wife will surely know who I'm talking about) who goes out of his way to teach me how to say entertaining (to him) things in Japanese. These have variously included obscure slang that even my Japanese wife doesn't understand, his Tokyo dialect attempt at Osaka dialect, Okinawan words, samurai-speak, and, of course, yakuza-speak, including such "gems" as throwing ora at the end of a sentence, which basically does nothing more than to indicate that you're pretty dang peeved, or "Nani gan kureten da yo?!", which would most appropriately be translated as "What the @#$% are you looking at?!" The two of us have gotten pretty good at going back and forth with the latter in faux anger and other Japanese speakers have suggested that we take our comedic duo on the road. As fun as that might be, I think I'll hang on to my day job for the time being.

Now, of course, I wasn't dropping such bombs as "Nani gan kureten da yo?!" in the tiff with my wife, but apparently my intonation and pronunciation started getting a little yakuza like. I think my faux-anger Japanese unintentionally permeated my real-anger Japanese, and she did not appreciate at all.

Point taken. But, I do have to say that, as a Japanese learner, it is kind of fun to get berated for speaking like a yakuza. Better that than getting berated for sounding like a foreigner!

(As an aside, my wife likes to watch The Sopranos with subtitles, because she has no idea what any of the Italian words they use are and some English words are new to her as well (today she learned "going on the lam"). I've come to love the subtitles as well because they're revealing a lot of the dialectical Italian that was spoken around me as I grew up that I could never figure out. My dad used to goofily say, "I'm one cool gubbagool," and even going over the various possibilities for how that might be spelled in standard Italian, I could never figure out what exactly it was. It turns out the word in standard Italian is capicollo, and it's some kind of meat. I'm still not sure what the heck my dad meant by "cool gubbagool"; he was a cold piece of meat? But then again he had a history of goofy little sayings, such as "lobster lips", which he lifted from a He-man with subtitles, because she has no idea what any of the Italian words they use are and some English words are new to her as well (today she learned "going on the lam"). I've come to love the subtitles as well because they're revealing a lot of the dialectical Italian that was spoken around me as I grew up that I could never figure out. My dad used to goofily say, "I'm one cool gubbagool," and even going over the various possibilities for how that might be spelled in standard Italian, I could never figure out what exactly it was. It turns out the word in standard Italian is capicollo, and it's some kind of meat. I'm still not sure what the heck my dad meant by "cool gubbagool"; he was a cold piece of meat? But then again he had a history of goofy little sayings, such as "lobster lips", which he lifted from a He-man episode I was watching.) episode I was watching.)Labels: dialects, Italian, Japanese, slang

Over on The Linguist on Language, Steve Kaufman "hazards a prediction" that the current economic crisis might lead to a crisis in confidence in the English-speaking world and that "it may not be such an obvious given that English has to be the international language." Steve also says that it's all in the attitude toward English, that it's a kind of fashion. I disagree with those two statements; it's not about attitude, it's about numbers, and the numbers show English very likely to remain the de facto lingua franca for a very long time to come. But before I back that up, let me first kick off with where I agree with Steve. I think we will see multilingualism on the rise. Part of it - and I agree with Steve wholeheartedly on this point - is that it's not a big deal to be multilingual, and I think more and more people are coming to that realization. I also think it's quite likely that certain languages might take on a regional nature. While I don't see German supplanting English in Europe, or Russian maintaining its preeminence for much longer in Eastern Europe among the Westward-facing post-Soviet Bloc generations, Chinese is a sure contender to gain some regional clout. The high ratio of Koreans and Japanese in my own and many others' Chinese classes in Beijing is a sure sign of this. And, generally, as the relative size of English-speaking economies decline as countries like China, India, and Brazil continue to grow, multilingualism undoubtedly will get a boost. That said, I don't think English is going to lose its spot as the world's de facto lingua franca to become just one of several important or regional languages. The numbers that best demonstrate this are how much of world GDP can be allocated to each language. What these numbers suggest is perhaps no major shocker: the continued dominance of the English language, albeit in a gradual decline, and the slow uptick of Chinese, with most other languages' positions not changing very much. Read more...Point by point, here's why I disagree with Steve.

First, the English-speaking world continues to maintain the largest portion of world GDP: around 30%. While this is gradually declining and will continue to do so for a long time to come before leveling off, it's likely to remain in the first position for quite a bit longer, and there's no foreseeable end to it being one of the top languages. Indeed, the only contender with the growth patterns to even possibly supplant English as the language representing the largest portion of the world GDP is Chinese, so at worst English will fall to second place. I believe that economic power correlates directly to the demand to study a language, as can be seen clearly in the widespread interest in English and the growing interest in Chinese.

Second, those statistics don't even consider those who speak English as a second language. Adding those in, it becomes clear why Latin Americans who meet with Arabs who meet with Chinese who meet with Japanese all tend to use English to speak with each other. I worked for a while in the Japanese legislature in the office of a representative with great connections with the Arab world, having attended college in Egypt. At one meeting with some Arab visitors, one Arab guest lamented that it was a shame that they had to conduct meetings in English, and some platitudes were jointly issued about learning each other's languages. While I haven't checked in on this issue lately, I'd be pretty content to wager a substantial amount of money on the fact that those meetings are in fact still going on in English.

Third, there are costs involved in switching from a single standard to multiple standards. If Japan actually sought to carry out the goal of reaching the general level of proficiency in Arab needed to carry out such meetings, countries speaking maybe a dozen other languages would line up for similar treatment. How much money would Japan need to spend to develop such a language proficiency in so many languages? Even if they just added Chinese and Spanish to the mix, you'd still be looking at much greater costs than the current Japanese set-up of a primary focus on English with other languages being more or less extracurricular. While there are certainly very strong arguments to be made that the money in Japan's language-learning efforts could be much better spent, the fact still stands that it will cost more to learn several versus just learning one.

Fourth, there's no obvious contender to take over as the world's lingua franca. Of all the other important languages, China is at about 13% and rising as a portion of world GDP and all the rest are no more than 7% and remaining relatively constant, and I don't think adding in second-language speakers would change those numbers greatly. And could you imagine Guatemalans meeting with Nigerians and conducing the meeting in Chinese? At this point, the idea is still laughable. Even regionally, there are few viable contenders aside from Chinese.

So, without knowing anything further about a student trying to pick their first foreign language to study, I would continue to give the same general advice I've been giving thus far: if your mother tongue isn't English, that should be your first target, as it remains the most economically useful of all languages.

Related: The (roughly) top 20 languages by GDP

When I saw this post on Steve Kaufmann's The Linguist, calling for tutors on LingQ, I jumped at the opportunity. I've been enjoying the "you scratch my back, I'll scratch yours" tutoring on sites like Livemocha and Live-8, so I wanted to give it a go on Steve's system as well. Tutors on LingQ get points and can cash out those points at $15/hour or use them on LingQ, and my points will surely be used to further my own language-learning goals. (Steve used LingQ to learn Russian. Perhaps I should finally make an attempt to take Russian off of my list of unfinished business...) While LingQ will certainly be up for a more thorough review by me after working with it some more, I can say right now that there's one feature I absolutely love. On LingQ, you copy and paste any text you want into it. When you highlight a word in that text and click a button, LingQ will look up the word for you automatically using Babylon's dictionaries or other free resources like Wikipedia, and then you can quickly make a flashcard (or what's called a "LingQ" in LingQ) by simply cutting and pasting. What a blessing that system is. For years, I've been taking my arbitrary texts (whether news articles, lyrics, or what have you) highlighting all the words I didn't know, looking up all the words, and then making flashcards. LingQ makes this exercise so much easier. The only downside is that you're limited to 300 flashcards on a free account, but if you can shell out (a pretty darn reasonable) $10/month, you'll have unlimited flashcards. To get back to my own LingQ tutoring, I'll be holding my first session next Monday on a topic everyone seems to be wagging their tongues about: this big, bad economic crisis. So, if you're studying English, feel free to get on there and look me up! Update Jan 15 2009 8:43PM: My username on LingQ is VincentPace (thanks Edwin!). Related: Livemocha review: Love the native speakers, the method not so muchLabels: English, Lang-8, language exchange, LingQ, Livemocha, Russian

I've recently been giving the totally free language-learning website Livemocha a spin. Livemocha is absolutely excellent for putting you in touch with native speakers and having them correct your written and spoken submissions, but its teaching method leaves a lot to be desired, and they still have some kinks to work out of the system. Livemocha divides a language into courses, then units, and then lessons. For most languages, there are four courses that aim to get you to an intermediate level, and each course is divided into three units of about five lessons each. Lessons, in turn, are divided into four types of activities: learn, review, write, and speak. Let me start with the last two and what I love about the site: how it links you up with native speaker tutors, and plenty of them at that. The "write" section asks you to write a short text, generally based on the lesson but you're free to meander off topic (and I frequently do), and the "speak" section asks you to read and record a passage of target language text. You then submit these to up to ten other users to correct for you. Read more...Ideally, you'll want to submit your work to be corrected by native speakers, but even among native speakers your feedback will vary greatly. I initially began by just randomly selecting German speakers from among my friends and the website-suggested users, but I was able to quickly discover and prefer those who were giving me the highest-quality feedback. I now have a core group of tutors to whom I consistently submit such assignments to, and their feedback is phenomenal. They drill into my work to find even subtle mistakes and offer excellent explanations of what I'm doing wrong. So, while initially you may find that the feedback you get is not all that great, as you separate the wheat from the chaff you'll eventually end up with excellent tutors.

The other way in which Livemocha connects you to native speakers is via chat. You can do text chat, audio chat, and video chat. Livemocha encourages you to chat via their system by providing you with points for using it (more on that below), but given the rough feel of their chat capabilities I often find that we end up taking it out of Livemocha to MSN for text chat and Skype for audio or video chat. Despite the issues with Livemocha's own chat features, it stands as an excellent tool for putting you in touch with native speakers of your target language.

And you might be wondering how it is these people will correct your work for free. Like certain other other language websites, they use a deviously clever all-carrot, no-stick point system. You get points for studying, but also for teaching, i.e., doing things like correct others' written work. After you submit in the writing or speaking sections, you're presented with another learner's work to be corrected in your own language. This is ingenious social engineering; right after you've asked a bunch of people to correct your work, you're presented another's work to correct. How can you not? You actually can skip it, but I'd bet the skipping rate is pretty low.

You'll also find that, once you have your established tutors in your target language, you'll be eager to correct any work they send you in a quid pro quo; they're doing a great job for you, so you feel the need to do a great job for them. My only gripe, and I suppose it's more of a request for improvement than a gripe, is that I'd like to be able to sort my requests for corrections by the number of times the sender has corrected my work. For now, I do it manually by just trying to remember who has been helping me out.

Now let's turn to the parts that don't impress me so much. The "learn" section of a unit consists of a picture being shown with the text describing that picture below and a native speaker speaking the text. It's not always clear what the text is describing, so you're provided with a translation button that lets you see what the text is supposed to say in your native language.

The "review" section consists of exercises, of which there are three types.- Read: You select the picture that matches target language text.

- Listen: You select the picture that matches target language audio.

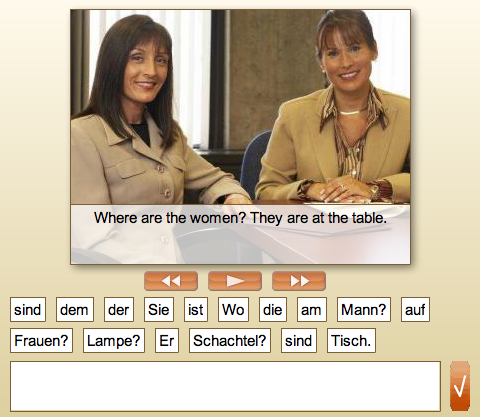

- Magnet: You put together a sentence magnet puzzle to match target language text or audio, which looks like this in the case of text:

Additionally, there are extra optional exercises, which include the above three plus "quiz" exercises, in which you are presented with a word, phrase, or sentence in the target language and must select the corresponding translation. Additionally, there are extra optional exercises, which include the above three plus "quiz" exercises, in which you are presented with a word, phrase, or sentence in the target language and must select the corresponding translation.

You can also make flashcards from the content in the lessons, or you can make your own flashcards from scratch. It's something of a hassle to make flashcards, and the testing method is the same as the "quiz" exercises, with incorrect answers selected from within the same flashcard set. These basic flashcards seem like something of an afterthought, and it's quite a hassle of pointing and clicking to make your own flashcards.

The core method is much like Rosetta Stone's; they provide you with the language, and you're supposed to figure out the rules.

As is always the case with such inductive systems, the problem is that that does not work very well for anything above a certain degree of complexity. I've been trying out Livemocha as a way to review German, and one of the issues I knew that I definitely need to review was the cases. The one-line explanation of German cases for the uninitiated is that certain German words, including nouns, adjectives, "the", "a", etc., change their form depending on how and after what they are used in the sentence. I had cases down pat before, but as I've not been using German a lot over the past few years the exact rules have slowly leaked from my head, and I thought I'd be able to pick them up using Livemocha.

But that was not the case. I frustratingly found myself making the same mistakes over and over again, and wishing I just had the rules presented to me so I could quickly refresh my memory. Ultimately, I turned to other websites and some grammar books I have to get a refresher. If this is the case for me, a person who is reviewing the rules, it would only be that much harder for someone taking their first crack at German to actually figure out what is going on in the grammar just by going through Livemocha's courses.

And I'm certainly unimpressed with the exercises' ability to actually test your knowledge. For one, you can often figure out the answer from words you learned earlier without needing to test the words in the most recent lesson. For instance, if you're studying adjectives, they might have "a fat man", "a skinny girl", "a tall boy", etc. But because they use a different noun for each, you can easily figure out what the answer is without knowing a thing about the adjective. Similarly, you can often use process of elimination to figure out answers, without really needing to understand what's being presented to you. For instance, pictures are often tested in groups of four. Once you've done the first three, you know the next answer will be the fourth. The same sort of process of elimination can be used in the magnet exercises. What's more, in the magnet activities, there is no tolerance for incorrect punctuation or the like. For instance, you might find "gut" and "gut." (i.e., one with a period and one without) as two separate magnets among the options. If you accidentally put the one without a period at the end of a sentence, it'll mark it wrong. While strictness has its place, this is most likely just a stupid mistake that doesn't reflect on your comprehension and hence should be ignored, but isn't.

Another practice I find suboptimal is their use of a single learning course for multiple languages. There is a core course that is simply translated to other languages to expand the system. While this makes it easier to incorporate more and more languages, it is not optimal for learning as the course will undoubtedly work better with some languages than others.

The last big group of issues with the site that I'll touch on are what appear to be growing pains: kinks that I would hope are temporary and will be worked out over time. These are the little things that take away from the experience.

Certain assignments ask you for things that haven't been taught yet. For instance, in German 101, Unit 2, Lesson 2, the writing assignment is "Describe the locations of a set of people and objects. Describe each. EX. The woman is on the yellow couch. She is not in the brown chair." However, up to this point the course has not covered how adjectives change in front of nouns. This means that your poor reviewers will have to correct all of your guesswork and it greatly increases the burden on them.

And the system still has mistakes outright in it. For instance, in one exercise, I came across this picture:

The text for this was "Wo ist er? Es ist im Karton." ("Where is he? It is in the box."). This is, of course, as wrong in German as it is in English, but it was that way in both the text and in the native speaker's recording. You would think that the native speaker would have at least flagged this for them so they could fix it instead of just reading it rote (if that was in fact a computer's voice, color me impressed). Another mistake I came across was "Der Junge hat keine roten Haaren" ("The boy doesn't have red hair"). The mistake is that there's no -n on the end of the word for "hair"; it should be Haare.

In addition to outright mistakes, there are also times when two or more pictures are the right answer, leaving you guessing blindly as to which one is actually the "right" answer. In the exercise below, the text says, "Where are they? They are in the box," and you've got to pick the correct picture. Well, are they referring to the candies in the box or the flowers in the box? It's totally unclear and you're left guessing which is supposed to be the right answer.

And here's another one. The text says "She doesn't have red hair." We can eliminate the guy and the lady with red hair, but which of the two non-redheads is this referring to? Only haphazard guessing will tell.

There is also generally bugginess in the responsiveness and behavior of the interface. There were a few times when I went through one "review" section and only got one or two wrong (out of 40) and ended up with a score like 70%. I can only attribute that to some sort of technical screw-up. There were at times time lags that resulted in incorrect clicking, and sometimes a click wouldn't register at all. This is particularly true when you have a Livemocha chat window open and are getting a new chat message.

Despite what now looks like a post full of griping and moaning, I would recommend Livemocha as a tool for language learners. Their teaching method is not all that great, but it's not terribly painful to click through a bunch of cards, and it's certainly helpful to hear the target language spoken by a native speaker. And, of course, you can skip it, if you want to. But the real gold lies in the site's ability to put you in touch with native speakers, and you should definitely arm yourself with that as one tool in your language-learning kit.Labels: German, Lang-8, language exchange, LingQ, Livemocha, native-speaker tutor

Happy new year! I've returned from a brief holiday hiatus with a resolution to bring you much language-learning goodness in 2009. To kick it off, I just ran across So you want to learn a language, which maintains copious links to all sorts of language-related websites, including both more general sites (like this one) and language-specific sites. The site is an excellent place to dig up resources for just about whatever language-related activity you care to partake in.

|

|